MAJOR FEATURE

Hospo Workers Wanted

Pushing through a pandemic and natural disasters, the pub sector is still weighed down by the continuing challenge for enough workers to get back to full speed.

In recognition of this challenge, PubTIC has spoken to groups of all sizes and states, to gather the wisdom of the brains trust and help find the solutions. Clyde Mooney reports

Australia: the wide, brown land of droughts and flooding rains, and monumental fires, and of course eventual participant in a global pandemic, leading to havoc in the population and in tourism – in a place traditionally reliant on the service dollar.

Sounds a little inhospitable.

Just as we fared somewhat better than most in shielding ourselves from the carnage of a rampant new virus, our isolation has assisted the rebound across most industries.

Australian job vacancies peaked at 369,900, in May 2021, and the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) cites seasonally adjusted estimates for April 2022 seeing the unemployment rate unchanged at 3.9%, and total employment increase to 13,401,700.

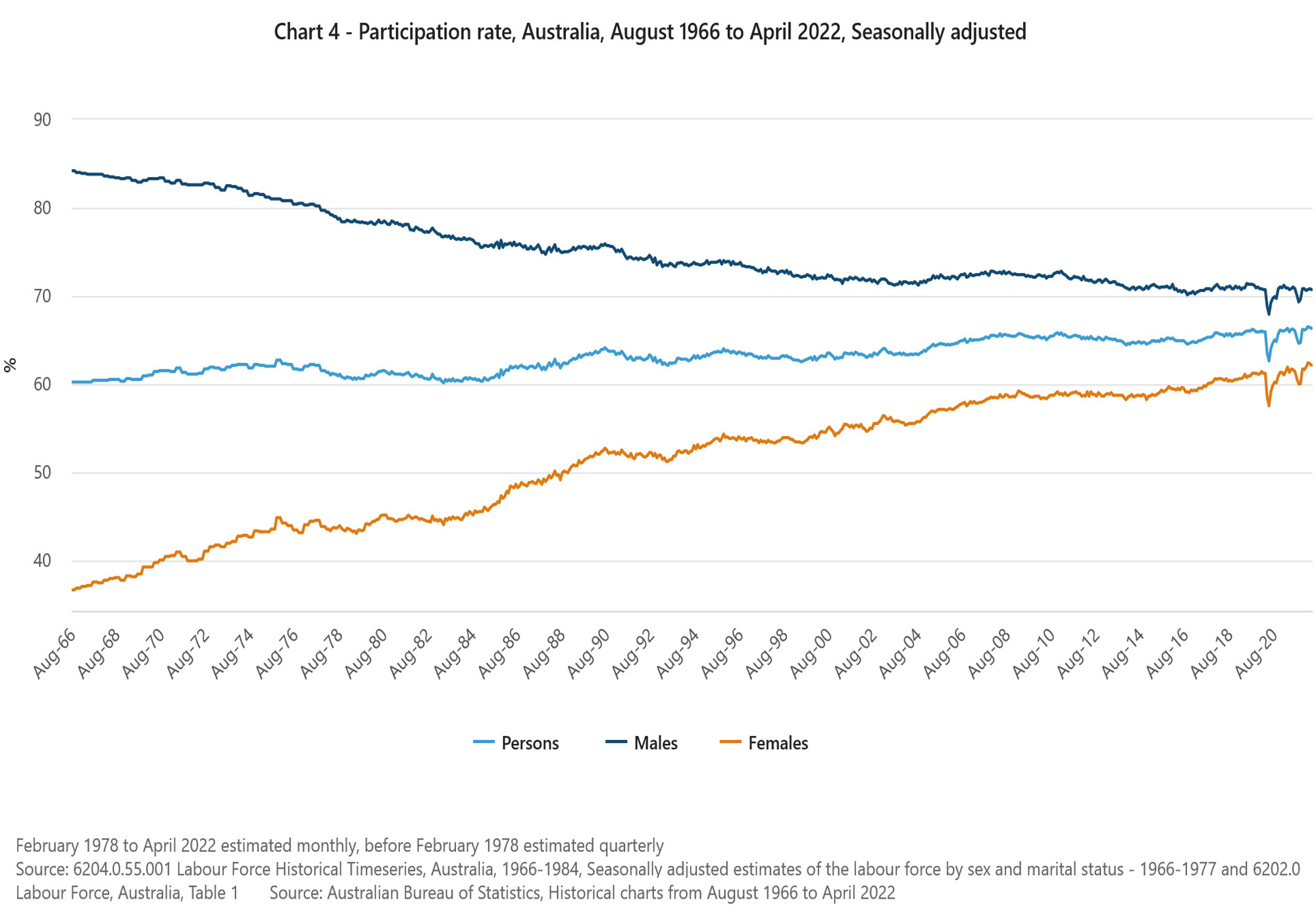

Interestingly, while the employment to population ratio remained at 63.8%, participation rate decreased to 66.3%.

Employment site Seek reports another month of job ad growth in April, rising an average of 2.9% nationally – representing the highest number of jobs posted since 1998.

And yet, applications per job ad decreased for the third consecutive month, dropping 7.6%, to be the lowest number of

applications since 2012. LinkedIn supports this, reporting the average number of applications per job down 63% compared to one year ago.

Recruitment startup Barcats reports a “mass exodus” of about 25% of hospitality industry workers, particularly skilled foreign workers such as chefs and managers.

It is perhaps no surprise then that the two largest industries by job ad volume (Trades & Services, and Hospitality & Tourism) each registered another decrease in job ads during April. In fact, applications per job ad remain significantly lower than pre-COVID – meaning it is more important than ever for employers to understand what workers are thinking and feeling.

How groups are faring

The staff shortage has hit all levels and types of operator. Justin Hemmes’ trailblazing Merivale revealed trading down 20% under the weight of 1,000 missing staff across the group – at least 25% down on the usual 4,500, with a chronic shortage of chefs, line level cooks, chef de parties, sommeliers and waiters.

Lewis Land, which owns such major operations as The Fiddler and Camden Valley Inn says it needs more suitably skilled staff, mainly kitchen hands and suitably qualified chefs, but also marketing and duty managers.

The Colosimo family’s Momento Group has reported staff shortages “across the board” and a drought on every level. Stephen Hunt’s group reports experienced kitchen staff as the most difficult roles to fill, followed by senior management positions.

MAJOR FEATURE

Paul Devine is chief operating officer for Iris Group, which counts assets across NSW including the Hunter Valley and Newcastle, as well as Lassiters Casino in the Northern Territory and now in Broadbeach, Queensland. Devine is responsible for all hospitality ventures and says the problem hiring enough staff is “far flung”.

In South Australia, the Hurley Group is finding issues with hiring “across all aspects of the business” – from housekeepers, to the most difficult to fill being qualified chef positions.

In Victoria, Melbourne doyen Sand Hill Road (SHR) is finding the way back to top gear, as positions for floor and bar staff fill up. Director Andy Mullins reports the lack of chefs and chef de parties is affecting them, particularly at their larger pubs, the Garden State and The Espy.

“We can’t open all our venues all the time for all sessions, but we’re down to needing about 50 staff, largely duty managers.”

Australian Venue Co is the second-largest pub group in the country, wielding 180 venues, and has applied significant head office resources to the lack of staff resources.

CEO Paul Waterson reports they are “not too bad”, in reasonably good shape having recruited around 1,100 people in the past three months – mostly newcomers to the industry, in front of house roles. This leaves their shortfall at about 5% of the full complement of 6,400.

Waterson admits Victoria is probably the most challenging state

for AVC. This is likely due to its volume of venues, but the state’s pandemic processes were a catalyst.

“Victoria went through the longest lockdown last year,” he says, “And there’s no doubt there was some movement of senior hospitality people to the other states.”

Research from employment sites is finding the roles most in-demand for Hospitality & Tourism (in order) were for chefs/cooks, management, waitstaff, bar and beverage staff, kitchen, and front office & guest services.

Why is this happening?

Seek puts the key reasons contributing to the decline in hospitality workers to: reduced labour supply, workers approaching career moves more cautiously, and more jobs available in other sectors.

For the industry more broadly, there is universal agreement that the movement of the visa workers back to their home countries at the start of the pandemic is a lingering blow.

Hunt Hospitality notes staffing issues hospitality businesses are facing include: wage to revenue ratios, staffing skills, and a general labour shortage as employees find more choice to pick and choose where they want to work.

These are all consequences of a post-pandemic population wanting more life/work balance.

Lewis Land cites how salary expectations are ever-changing.

The chart shows the interconnectivity of the male and female workforces, and that while thousands of Australians dropped out of the workforce during the major shutdowns (43,300 in April 2020), they have returned.

MAJOR FEATURE

“We know employers are incentivising people to stay with them, so the pool of skilled candidates is very shallow.”

SHR, which has its collection of pubs in Victoria, had a front row seat to the effects of the world’s longest lockdown and says it rocked worker security.

“You cannot lock down a city that’s really only known for its arts and hospitality for two years and expect that people are going to be thrilled to have the opportunity to be locked down again,” says Mullins.

“We are also seeing hugely inflated wages that we just can’t meet – and it doesn’t feel fair to all those that have stuck with us, to fill new roles at that rate. We’ll be cautious and slow about the build.”

Iris CEO Devine holds a unique perspective beyond the group’s multi-state footprint. Born in Ireland, he came to Australia as a backpacker two decades ago, drawn to the country’s reputation on employment and favourable working agreement with home.

The son of a publican back in Ireland, he grew up in an industry held in high esteem. In the early 2000s he joined the ranks of UK and Irish workers headed Down Under. Starting as a bartender, he rose to become a duty manager for Gallagher Hotels, learning gaming (foreign to most Europeans) and completing a hotel degree. Rising through the ranks he now heads Iris’ ever-expanding collection of pubs.

Devine observes the influx of youth from his home region was followed by a similar wave from India and then Nepal. Recent years have found the labour market in Australian hospitality 80% foreign-born workers, leaving it in a precarious vacuum as non-citizens are effectively evicted.

“Once you kick people out, they’re not in a great rush to come back,” says the Iris CEO. “When you rely on foreign labour and you do that, it’s a serious issue.

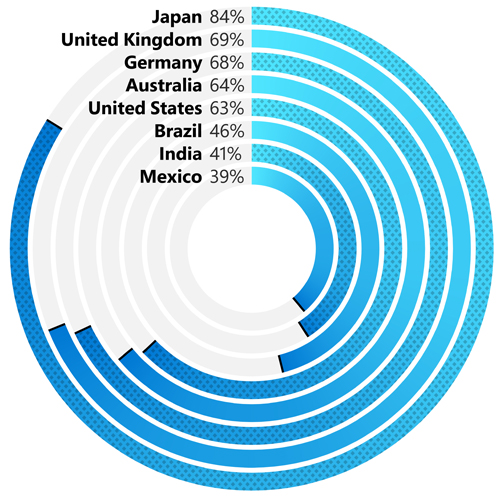

Global research by Microsoft finds Australia midway in the list of countries where hospitality workers report increasing levels of stress in the workplace. Australia comes out worse than the USA, despite America’s reputation for poor job security for frontline workers and comparative lack of social support during the pandemic.

“We haven’t grown a local talent pool in 20 years, and this reliance creates a big dilemma; when there’s no jobs for the local market, why would locals endeavour to get into it?”

Hurley Group sees the lack of training as not a new problem.

“There are so many long- and short-term reasons for these shortfalls,” says Anna Hurley.

“In the case of qualified kitchen staff it has been ongoing for years, due to the stale and outdated training model for commercial cookery. This has then been exacerbated by the COVID pandemic, where qualified people left for greener pastures while hospitality was labelled high risk by our politicians.”

AVC is finding a distinct undersupply in roles such as venue mangers and assistant managers, and head chefs, which Waterson sees as largely a result of the disruption.

“Normally you’d be undertaking training and succession planning for these people. But over the last two years that’s been interrupted, so you’ve had a period whereby there hasn’t been as much training and development and experience of this next generation. The periods of closure mean they’ve not been coming up through the ranks, so you’ve got that gap now.”

MAJOR FEATURE

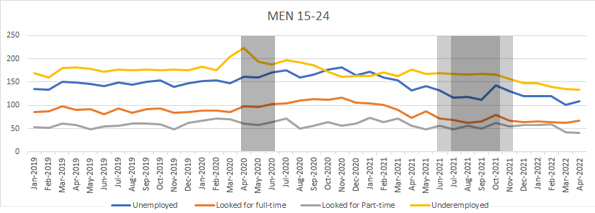

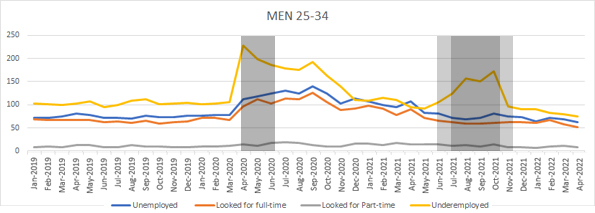

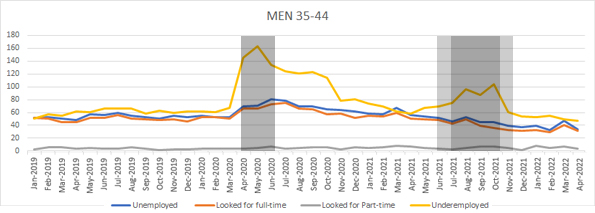

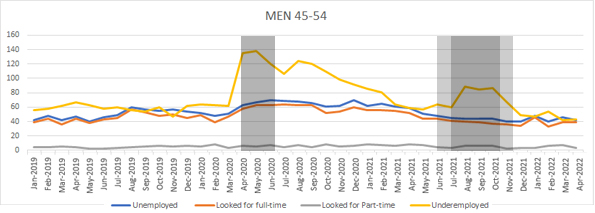

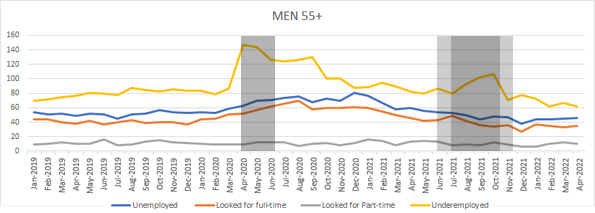

ABS data of Australian workforce for men between January 2019 and April 2022 of all ages

MAJOR FEATURE

MEN

*Grey shaded areas represent major shutdown periods

*Scale = ‘000s

In 2022 to date, all age groups show a marked decline in men counting themselves as Underemployed

The figures for Underemployed show that while there was a major spike during the 2020 lockdown across all age groups, the spike during the 2021 lockdowns did not cause as much disruption to male workers, who had presumably found employment less susceptible to the closures

- Similarly, while all age groups show an increase of men looking for both Full- and Part-time work during the first lockdown, all age groups (except under 25s) continue to show falling numbers looking for Full- and Part-time work during the second lockdown

- Unlike other countries (particularly the US), where a lot of hospitality workers hold more than one Part-time job, all age groups (except under 25s) report low numbers of people looking for Part-time work. This could represent an opportunity for Australian hospitality employers, hoping to fill shifts with flexible workers

MAJOR FEATURE

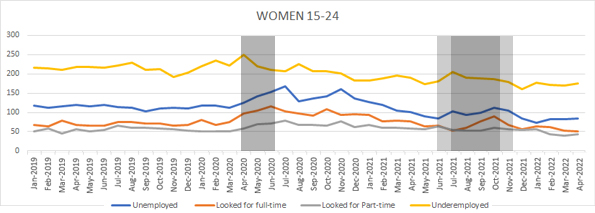

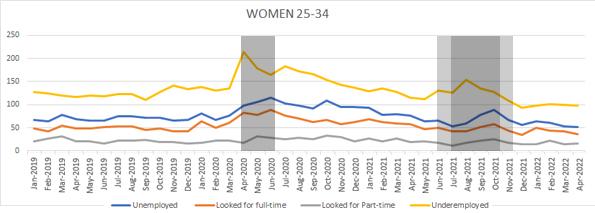

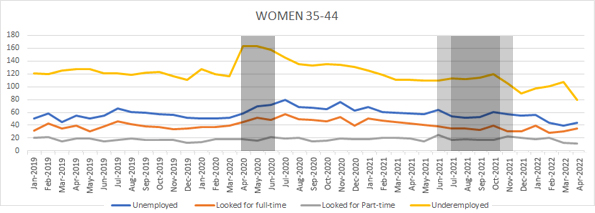

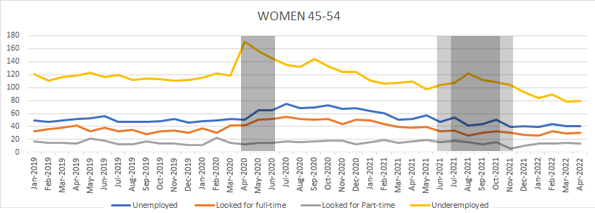

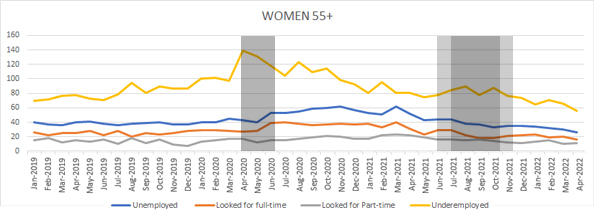

ABS data of Australian workforce for women between January 2019 and April 2022 of all ages

MAJOR FEATURE

WOMEN

*Grey shaded areas represent major shutdown periods

*Scale = ‘000s

- As with men, all age groups show a marked decline in 2022 in women counting themselves as Underemployed

The number of women looking for Full- and Part-time work and counting themselves Underemployed declined this year across all age groups except 35-44

- There was significantly less of a spike in women counting themselves as Unemployed or Underemployed during both shutdown periods, as more temporarily removed themselves from the workforce (participation rate not available across age brackets)

Women 35-44 are also the only bracket that shows higher rates in looking for Full-time work and Unemployment than prior to the sample period (beginning January, 2019)